China's arc of instability

China now has its own "arc of instability". After bloody uprisings in Tibet and Xinjiang, renewed insurgency in Afghanistan and a threatening destabilization of its ally Pakistan, Chinese experts see a "very high risk of a return to widespread armed conflict along the China-Myanmar border" that causes additional problems for the central government as well as testing its humanitarian stance.

Yesterday, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Jiang Yu urged Myanmar to maintain stability in its border-region along Yunnan province after clashes between the military regime and local self-governing authorities provoked about 10.000 to 30.000 refugees (other sources speak of up to 50.000, mainly from the ethnic Chinese group of Kokang, flooding into China. Employing an unusual direct language, Xinhua wrote that "China hoped Myanmar could properly solve its domestic issue to safeguard the regional stability". The NYT reported that the fighting, making thousands fleeing over the Chinese border, already began in early august. Possibly, the intensifying military operation against the Kokang army (and other autonomous ethnic groups) that expanded into Chinese territory killing a civilian results from a strategic shift by the Myanmar's ruling generals and unfolds against the communist parties warning not to disturb the National celebrations on Oct. 1 (for more on the background see here and here). Whereas the USA government is deepening its communication with myanmar's junta, Chinese government seems to loose leverage on its neighbor's regional policies.

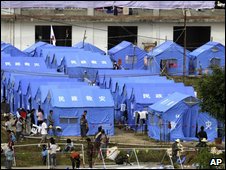

Refugee camp in Nansan, Yunnan Province, BBC.

According to Xinhua, "Yunnan is helping them settle down in seven settlements with supply of life necessities, medical care and disease control measures as humanitarian assistance". Building a refugee camp, for the first time, China has to handle a huge refugee crisis (if we don't count the continuous stream of refugees from North Korea for a moment) within its own borders. While currently available information show how much the country's policies seem to be rendered by "international standards", we don't know the exact situation, neither in the almost inaccessible northern parts of Myanmar nor in Yunnan's vast border-areas. Thus, it is still to early to make some broader judgements. Yet, in any case, the initial official reactions of Chinese authorities display a remarkable concern for citizens involved, both Chinese and Non-Chinese. How China deals with the masses of refugees also sheds light on its possible future treatment of contingencies like a sudden breakdown of its other despotic neighbor North Korea.

Also, this event reveals that Chinese foreign policy is no longer based on the traditional formula of "non-interference" - a shift that is in the making at least since 2008, when China, under heavy pressure by NGOs and US-American movie stars, openly intervened in Sudanese politics. Even if Beijing will not openly join the interventionist tendencies by invoking the "responsibility to protect" any time soon, it remains no longer unthinkable that the Liberation Army may take part or even lead a UN peace operation in northern Myanmar. In the case of such a military operation, given that Myanmar's government will not solve the problem of military independent groups along the border areas "once and for all", as some commentators speculate, China would not cooperate on a governmental level as with Central Asian states through the well-established multilateral framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The rational, then, would rather be based on the idea of a fragile state to be rebuilt. In this sense, China's emerging arch of instability could work as a catalyst for her full-fledged inclusion into international nation-building missions. Beijing's own "unfinished" nation-building projects in Tibet and Xinjiang, however, are at crossroads leading the government into the quagmire of multiple, mutual reinforcing conflicts along this (south) western peripheries.

International Crisis Group provides a brand new report about "Chinas Myanmar Dilemma".

Yesterday, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Jiang Yu urged Myanmar to maintain stability in its border-region along Yunnan province after clashes between the military regime and local self-governing authorities provoked about 10.000 to 30.000 refugees (other sources speak of up to 50.000, mainly from the ethnic Chinese group of Kokang, flooding into China. Employing an unusual direct language, Xinhua wrote that "China hoped Myanmar could properly solve its domestic issue to safeguard the regional stability". The NYT reported that the fighting, making thousands fleeing over the Chinese border, already began in early august. Possibly, the intensifying military operation against the Kokang army (and other autonomous ethnic groups) that expanded into Chinese territory killing a civilian results from a strategic shift by the Myanmar's ruling generals and unfolds against the communist parties warning not to disturb the National celebrations on Oct. 1 (for more on the background see here and here). Whereas the USA government is deepening its communication with myanmar's junta, Chinese government seems to loose leverage on its neighbor's regional policies.

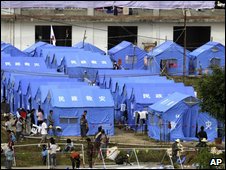

Refugee camp in Nansan, Yunnan Province, BBC.

According to Xinhua, "Yunnan is helping them settle down in seven settlements with supply of life necessities, medical care and disease control measures as humanitarian assistance". Building a refugee camp, for the first time, China has to handle a huge refugee crisis (if we don't count the continuous stream of refugees from North Korea for a moment) within its own borders. While currently available information show how much the country's policies seem to be rendered by "international standards", we don't know the exact situation, neither in the almost inaccessible northern parts of Myanmar nor in Yunnan's vast border-areas. Thus, it is still to early to make some broader judgements. Yet, in any case, the initial official reactions of Chinese authorities display a remarkable concern for citizens involved, both Chinese and Non-Chinese. How China deals with the masses of refugees also sheds light on its possible future treatment of contingencies like a sudden breakdown of its other despotic neighbor North Korea.

Also, this event reveals that Chinese foreign policy is no longer based on the traditional formula of "non-interference" - a shift that is in the making at least since 2008, when China, under heavy pressure by NGOs and US-American movie stars, openly intervened in Sudanese politics. Even if Beijing will not openly join the interventionist tendencies by invoking the "responsibility to protect" any time soon, it remains no longer unthinkable that the Liberation Army may take part or even lead a UN peace operation in northern Myanmar. In the case of such a military operation, given that Myanmar's government will not solve the problem of military independent groups along the border areas "once and for all", as some commentators speculate, China would not cooperate on a governmental level as with Central Asian states through the well-established multilateral framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The rational, then, would rather be based on the idea of a fragile state to be rebuilt. In this sense, China's emerging arch of instability could work as a catalyst for her full-fledged inclusion into international nation-building missions. Beijing's own "unfinished" nation-building projects in Tibet and Xinjiang, however, are at crossroads leading the government into the quagmire of multiple, mutual reinforcing conflicts along this (south) western peripheries.

International Crisis Group provides a brand new report about "Chinas Myanmar Dilemma".

MaxM - 29. Aug, 13:04